Sugarbush Management

Wriggling little pests have something to chew on

Caterpillars make way up northern Maple Belt

By PAUL POST | OCT. 3, 2017

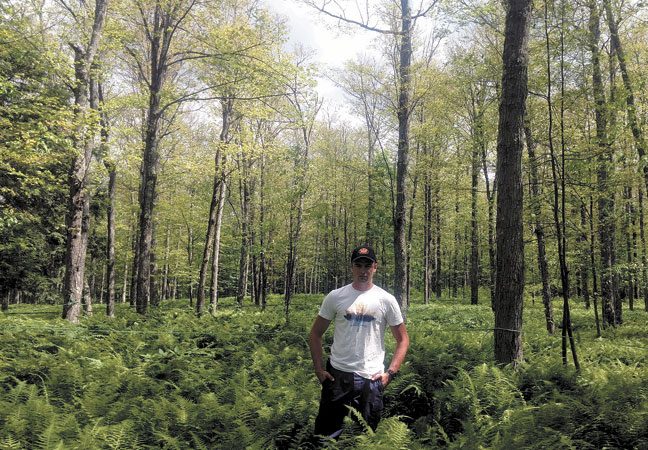

David Smart is used to seeing the sun shine down through treetops when sap starts flowing in his northern New York sugarbush. In July, there’s normally have heavy green canopy overhead.

But not this year as an unprecedented infestation of forest tent caterpillars has stripped trees of their leaves, creating a scene that looks more like early spring instead of mid-summer. Hundreds of acres throughout the North Country have been affected by the wriggling little pests.

“There’s got to be thousands of them,” said Smart, co-owner of Rand Hill Maple in Altona, Clinton County, N.Y., northwest of Plattsburgh. “I couldn’t believe it. I’ve been in the maple business 31 years. I’ve never seen this before. Ninety percent of the leaves are gone off hard maples.

“Right by the sugarhouse about 100 acres of trees were all stripped within two to three weeks, plus more than 700 acres I rent about 15 miles away. It’s not looking good.”

About half of his 60,000 taps have been impacted.

“There’s sun everywhere in the woods,” Smart said. “Whatever leaves are left are drying right up. It doesn’t look like the maples are coming back like the ash are.”

Economic impact

Despite the obvious cause for concern, an industry expert says the caterpillars are more of a nuisance than anything, and that the economic impact will likely be minimal. “Forest tent caterpillars are a native pest,” said Mark Isselhardt, Extension maple specialist at the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center. “It’s something that’s there in the background all the time. Yet trees are quite resilient. They store abundant amounts of carbohydrates.”

He compared trees to an ATM or bank account. Carbohydrates are stored as starch (savings) which is converted to sugar (cash), the lifeblood of the maple industry. Without leaves, trees experience less capacity for photosynthesis. “The biggest impact is significantly lower radial growth,” Isselhardt said.

Possibly, some sap might not be quite as sweet next spring. But so many things contribute to this, such as weather and soil conditions, that it’s difficult to gauge the affects of a tent caterpillar outbreak on syrup quality. “Like a lot of biological things, it’s complicated,” he said. “It’s just not well known. There’s no clear-cut formula. The amount of sap flow is not going to be affected at all.”

Tent caterpillars tend to be cyclical in nature. The most recent large infestation in 2006 affected 350,000 acres in Vermont alone, plus parts of New York, New Hampshire, Ontario and Quebec.

Last year, about 26,000 acres in Vermont were impacted. This year, as much as 55,000 acres have been chewed by the pests, according to state foresters.

It’s obvious that tent caterpillars don’t have long-term, dramatics affects on maple production because the industry has had record-setting, banner years this decade. “I’m just going to let nature take its course because I went through this before, about 15 years ago in Granville (Washington County, N.Y.),” said Mike Bennett, who’s currently setting up a producer’s sugarbush in Ellenburg, N.Y., near the Canadian border. “If trees die, it might be because they already have another problem. Trees have a life cycle, too.”

Even in the hardest hit areas, tree mortality from tent caterpillars shouldn’t exceed more than three percent, nowhere near the amount of defoliation. If anything, this could have the positive effect of ridding forests of weak trees, giving healthier ones more room to grow. Tree mortality is most apt to occur in combination with other stressors such as poor, calcium-deficient soil, Isselhardt said.

Pesticide defense

After peaking, the caterpillar population tends to rapidly decline on its own from two naturally-occurring forces — a virus and a fly that plays a parasitic role on the caterpillar cocoon.

The only approved human management technique is the biological pesticide, Bt, which is sprayed from the air. Some years, state and federal dollars have paid for applications in Vermont. That wasn’t the case this year, although state officials helped facilitate such efforts for producers who were willing to put up their own money.

“Sixteen sugarbushes were treated this spring,” Isselhardt said. “It looks like for the sugarmakers who did spray, their trees really benefited. But there’s a real narrow window for doing this, and it’s expensive.”

Andy Naylor, a sugarmaker in Johnson, Vt. treated about 200 acres this spring, at a cost of $25 per acre.

“I couldn’t be happier,” Naylor said. “It was well worth the money.”

Spraying can’t be done until after leaves, the caterpillars’ food source, start to emerge. Also, it must be done early enough when caterpillars are still small, and most vulnerable to the chemical’s impact. Caterpillars have five stages and larger ones are more resistant.

Caterpillar egg clusters can be detected in winter on tree limbs. Egg mass inventories, taken with binoculars, can be taken to predict the following year’s anticipated defoliation. People can do this on their own, or with help from professional foresters.

Surveys help determine the areas that should be given the highest priority for spraying.

“Even if you do nothing, the population of caterpillars is going to crash,” Isselhardt said. “It’s a natural cycle. It might take a few years.”

Tips for producers

In the hardest hit areas, a reduction in radial tree growth may persist for several years, even when caterpillars are no longer present because it takes time for trees to ramp back up after having leaves stripped in successive seasons.

Isselhardt offered tips to producers who are concerned about the health of trees that have suffered severe defoliation. They could take a year off from tapping, to help trees rebound, but that’s not financially practical.

So producers might want to consider using fewer taps — not putting multiple taps on mature trees, and increasing the minimum diameter of young trees they tap. “The smaller the tree, the greater percentage of its resources you’re taking,” he said.

Bradley Decoste, of Decoste Maple Farm in Mooers Forks, N.Y., said about 4,000 of his operation’s 12,000 tops have been affected by this year’s tent caterpillar outbreak. “Some of the sugarbushes took it hard,” he said. “There’s nothing but sunlight. I’ve never seen anything like this. But I guess in time they’ll come back. Maple trees are pretty tough. I think they’ll rebound.”

Originally published in The Maple News in Aug./Sept. 2017.