Candy & Cream

Candy Research, Part 2

Finding the right temp can help improve quality

By BY STEPHEN CHILDS CORNELL | MAPLE PROGRAM IN COOPERATION WITH MERLE MAPLE WITH MERLE MAPLE | JANUARY 2016

This article is a follow up of the article Maple candy research part I.

Reading that article first may make the experiments discussed in this article make more sense. The goals of this project are to improve the overall quality of maple sugar, molded maple sugar, maple sugar pieces or maple sugar candy which ever name you may be using. Quality is identified in terms of the smoothness to graininess, too soft to firm to too hard, length of shelf life and lack of white spots deep in the pieces to white dusting on the candy surface to no white spots.

The second goal is to improve the labor efficiency of making and handling the pieces. The majority of research was conducted on the water jacketed gear pump machine put together by Sunrise Metal Shop. With this unit the temperature of the funnel and piping can be set with a thermostatically controlled heating element in the water jacket. The experiments were a cooperation between Merle Maple in Varysburg NY and the Cornell Maple Program.

These experiments are not yet at the point of suggesting a proven system that will give you exactly the sugar piece you want but rather to gain insight and a better understanding of what the results are when certain steps are practiced so that maple producers can work to further improve the quality of their products.

With the goal of making a very smooth yet firm sugar piece with no white spots, conflicts in the processing temperatures soon become obvious. To make a very smooth candy the temperature of the syrup when it is first stirred is very important with the experience being that the cooler it is stirred the smoother the texture will be.

For dealing with white spots, if the stirred mix goes into the mold at about 150°F or less no white spots “usually” appear. The other factor seems to be if the temperatures in the mix going into the molds are variable white spots are likely to appear. If the sugar candy pieces are going to be consumed soon without a lot of handling the firmness of the candy is fine at around 150°F for stirring and mold filling.

However this candy is often too soft for bulk handling. It can be too easily crushed or broken in handling. This next set of experiments takes a step back from trying to be the most labor efficient to see if by doing different steps in the processing at different temperatures we could get that smooth yet firm candy piece with no white spots.

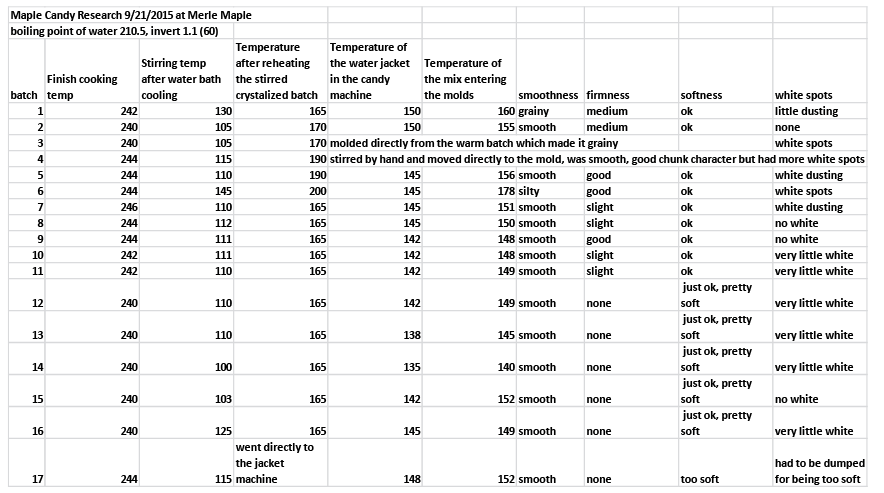

In this experiment the candy was first cooked to a finish temperature, cooled to a desired temperature, stirred in a commercial mixer until completely crystalized, re-heated and re-stirred with a commercial mixer then processed in the water jacketed gear pump candy machine, which also sets a temperature of the mold filling.

♥

First take a look at treatment number 1 (see chart on facing page) where the syrup was cooked to 244°F then cooled to 115°F and run directly into the water jacket candy machine. Even though it was cooked to the higher side of the normal candy finishing range, by stirring it so cool (115°F) as it first went through the gear pump it was too soft to even get out of the molds.

Even though it went into the molds at 152°F which it warmed to from 115°F due to the heat in the water jacket and the heat of crystallization, it’s temperature when the stirring begins sets the smoothness and the firmness. In every test after this the batch was brought up to finish temperature, cooled in a water bath, stirred in a commercial mixer until fully crystalized then reheated in that same pan and significantly returned to liquid while being stirred.

In batches 2 through 7 the temperature to which it was reheated and returned to liquid was gradually increased to see how the finished sugar pieces would change. First it was noticed that under these conditions if the batch after being cooled in the water bath was warmer than 125°F the finished candy would have a silty or grainy texture.

Normally when candy is not crystalized then reheated candy would not have a grainy texture until it was above 165°F or so. With the bath reheated to 165°F or above it had good firmness and could be bulk handled. With the water jacket at about 150°F, the syrup from these heated batches was going into the molds at between 155°F and 178°F giving mild to significant white spots on the finished candy.

Heating the batch the second time gave good firmness to the finished pieces but it seems it would need to be cooled more than what a few minutes in the water jacket offered due to the extra heat.

Batch 4 was a smaller sample taken from batch 3, hand stirred and put into the mold without going through the candy machine, without the second cooling offered by the candy machine water jacket it was grainy and had white spots. Batch 5 was a small sample taken from the batch 6 and put directly in the mold, it was silty textured, very firm and had white spots.

In all the rest of the batches the temperature of reheating was limited to 165°F as higher temperatures caused white spots and some poor textures.

In batches 8, 9 and 10, the finish cooking temperature was tested at 244°F and 246°F, each was cooled to about 111°F stirred in the commercial mixer, reheated and stirred to 165°F and placed in the candy machine where the water jacket temperature had been cooled to about 145°F.

Temperature entering the molds was dropped from 151°F for batch 8 down to 148°F for batch 10. Here the firmness was acceptable, the candy was smooth textured and only batch 8 showed slight white spotting looking more like a surface dusting.

Batches 11 through 17 were cooked to a finish temperature between 240°F and 242°F, cooled to between 125°F and 100°F, stirred in a commercial mixer, reheated to 165°F while re-stirred with a commercial mixer, added to the candy machine where the temperature in the water jacket was in the mid 140°Fs and entered the molds in the 140°Fs.

All of these batches had what we called very slight firmness with the softness being just ok and very minor white dusting that was not considered a problem.

♥

This system seems to have solved the problem of having batches so soft that they would not come out of the molds and unacceptable for handling bulk. It also is able to make candy pieces that do not have significant white spots. The labor involved in this system is more though it probably sounds worse than it is having the commercial mixers accomplishing much of the extra work.

In some ways this system has characteristics similar to the fondant methods described in Maple Candy Research I only the fondant making is not done a day or week ahead it is part of the process described here done all at the same time.

As we continue to look for ways to meet our goals of smooth, firm maple sugar pieces with no white spots several promising options remain to be tested. This includes using microwave to reheat batches that have been crystalized. Heating crystalized batches from the edge of the pan creates uneven temperatures that can lead to white spots and it requires continuous stirring during the heating so syrup on the edge does not get too hot and scorch.

The other is vacuum cooling freshly cooked batches of candy. Vacuum cooling speeds up the cooling process and evenly cools the whole batch which may get away from the white spots created by uneven temperatures in the process. That means you should watch for Maple Candy Research III at some point in the future.